Syllabuses’ content is up to professors

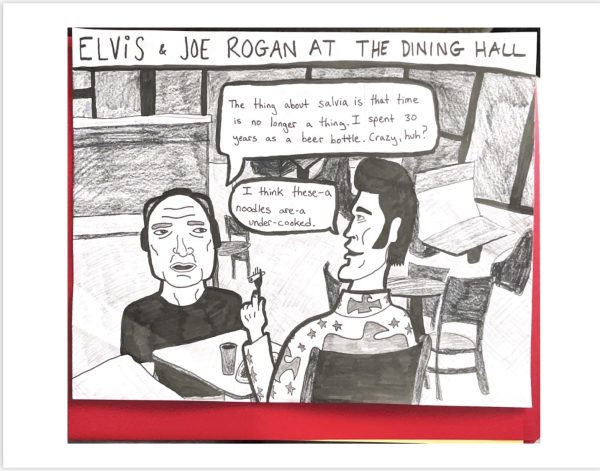

Junior Morgan Shumaker reads through homework for her Mass Communication Process course.

January 18, 2017

Since his time as a college student, philosophy professor Martin Rice said he has noticed a change in syllabuses.

“When I was an undergraduate, there were syllabuses distributed only rarely.

“You came to class and the professor told you where you were heading, what to read next, when there would be a quiz or a paper due.”

Rice has been teaching at Pitt-Johnstown for 26 years, and he said that he noticed how syllabuses have become more detailed over time.

According to communication professor Paul Lucas, this syllabus difference is a result of changing environments and changing students.

“I end up adding things (to the syllabus) rather than taking things away.”

This change, according to Rice, occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“It was a change from the mythos of the liberal arts … to the mythos of the insecurity of the small-minded business bureaucrat … a change from a broad-minded liberality that embraced the unknown to a small-minded fear of impecunious (financial) failure.”

Rice said, when he was an undergraduate, assignments were based on when a professor felt it necessary to a class.

“No two classes evolved the same way, so the evolutionary need for assignments based on the evolving needs of the class could not be predicted beforehand.”

Rice’s Introduction to Philosophy syllabus covers common topics such as attendance and cellphone policies, text requirements and an overview of class topics.

He said he doesn’t plan on changing his syllabus, because a syllabus’ main purpose is to cover the general direction of a course, and his does so.

Professors are able to create their own syllabus ideas and formats because they are allotted academic freedom, according to Humanities Division Chair Michael Stoneham.

“One of the freedom (university members) embrace is the idea of academic freedom: Professors have latitude and freedom in whichever way they choose.

“While certain division chairs might provide some guidance, it’s ultimately up to the professor to create their own syllabus.”

Stoneham said that his syllabuses are created in a way that benefits students.

“I want to tell students what text we’ll read and, by lesson, give students a sense of work required.”

Senior Lindsay Finnegan said that as long as a syllabus includes assignment and exam dates, she’s happy.

“I like being ready for what is going to be going on that semester.”

Junior Morgan Shumaker said that she reads through her syllabuses because attendance and assignment policies can vary.

“It doesn’t bother me that professors have different formats for a syllabus.

“Most of the professors I have usually have the same format, but it doesn’t bother me because, even if a syllabus is different, I can still find out information I need for the course and professor’s policies.”

According to Lucas, standards like cellphone policies and assignment guidelines are considered while creating syllabuses.

Academic freedom that provides professors a chance to create their syllabus the way they want, is an aspect that Lucas said he appreciates.

“I’ve never been told to do things certain ways … I like having the freedom to do my policies the way I want.”